Footage of world's largest plastic 3D printer printing pedestrian bridge

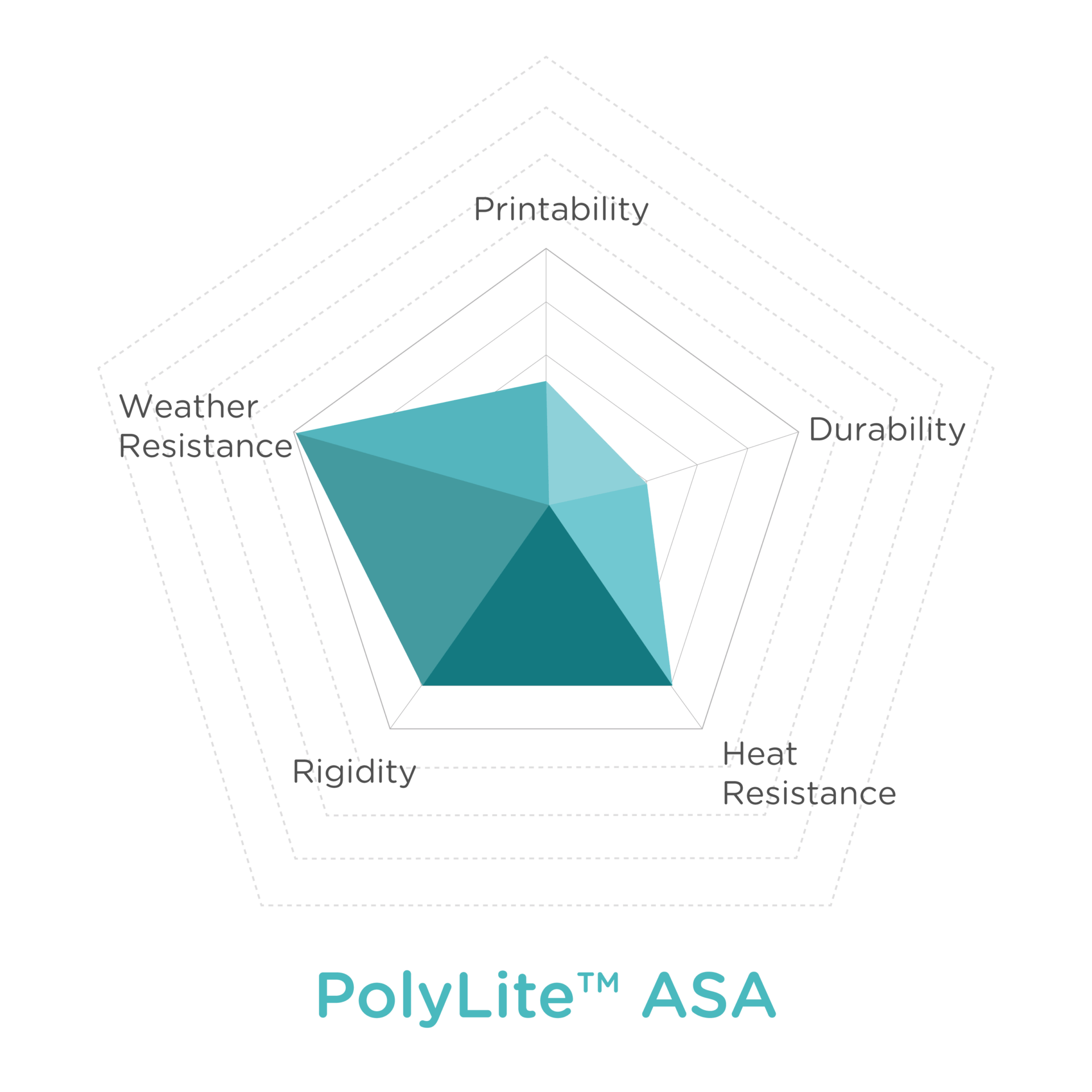

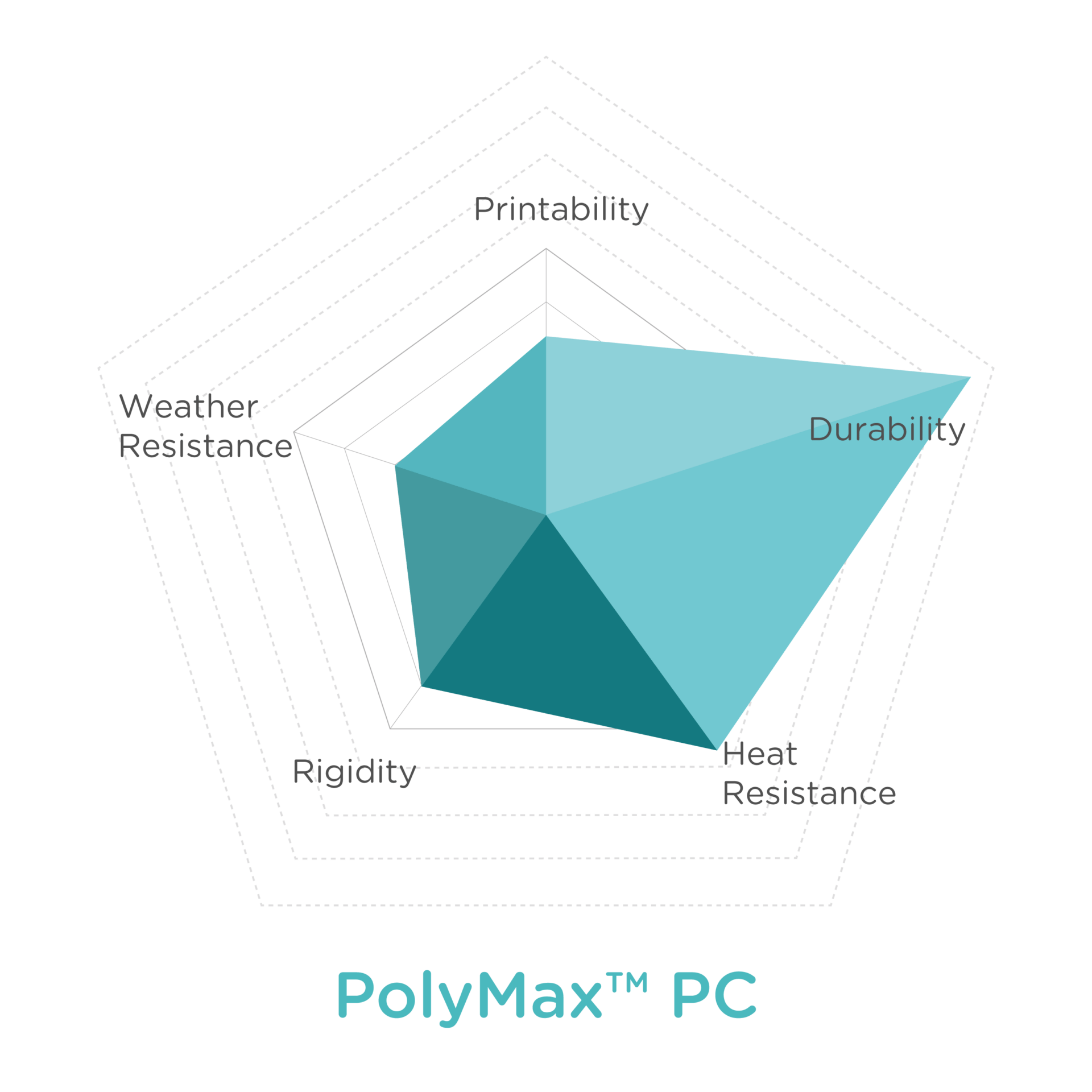

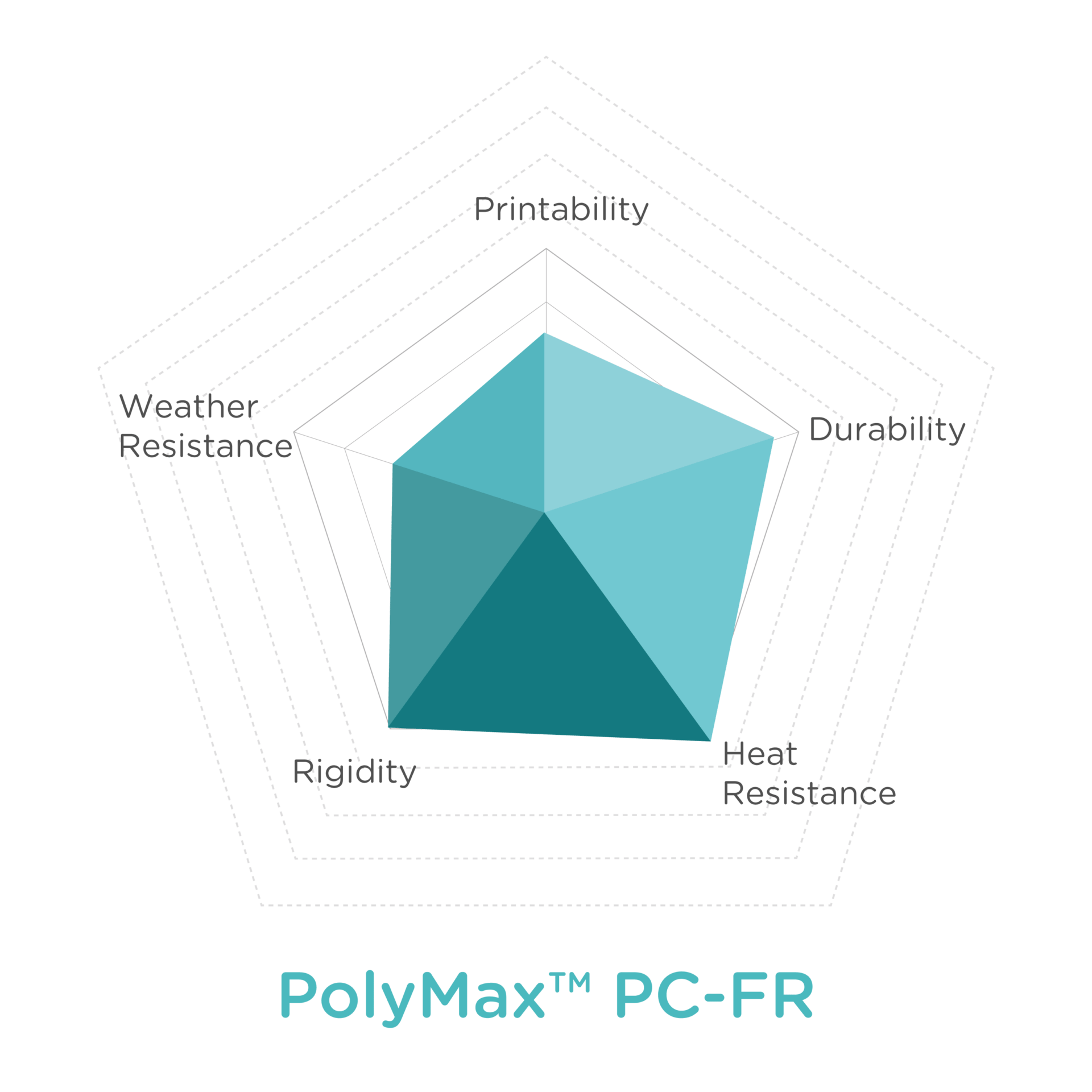

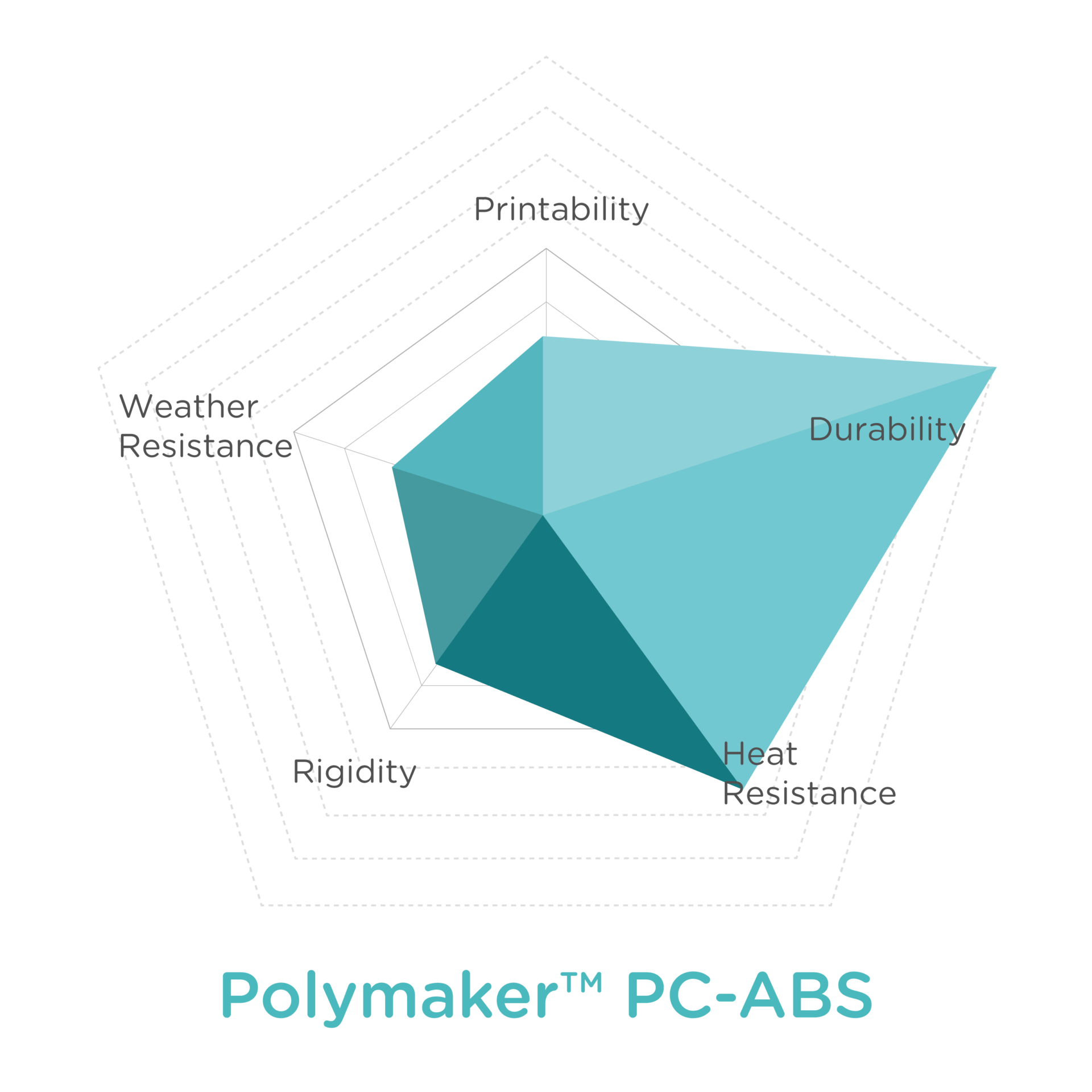

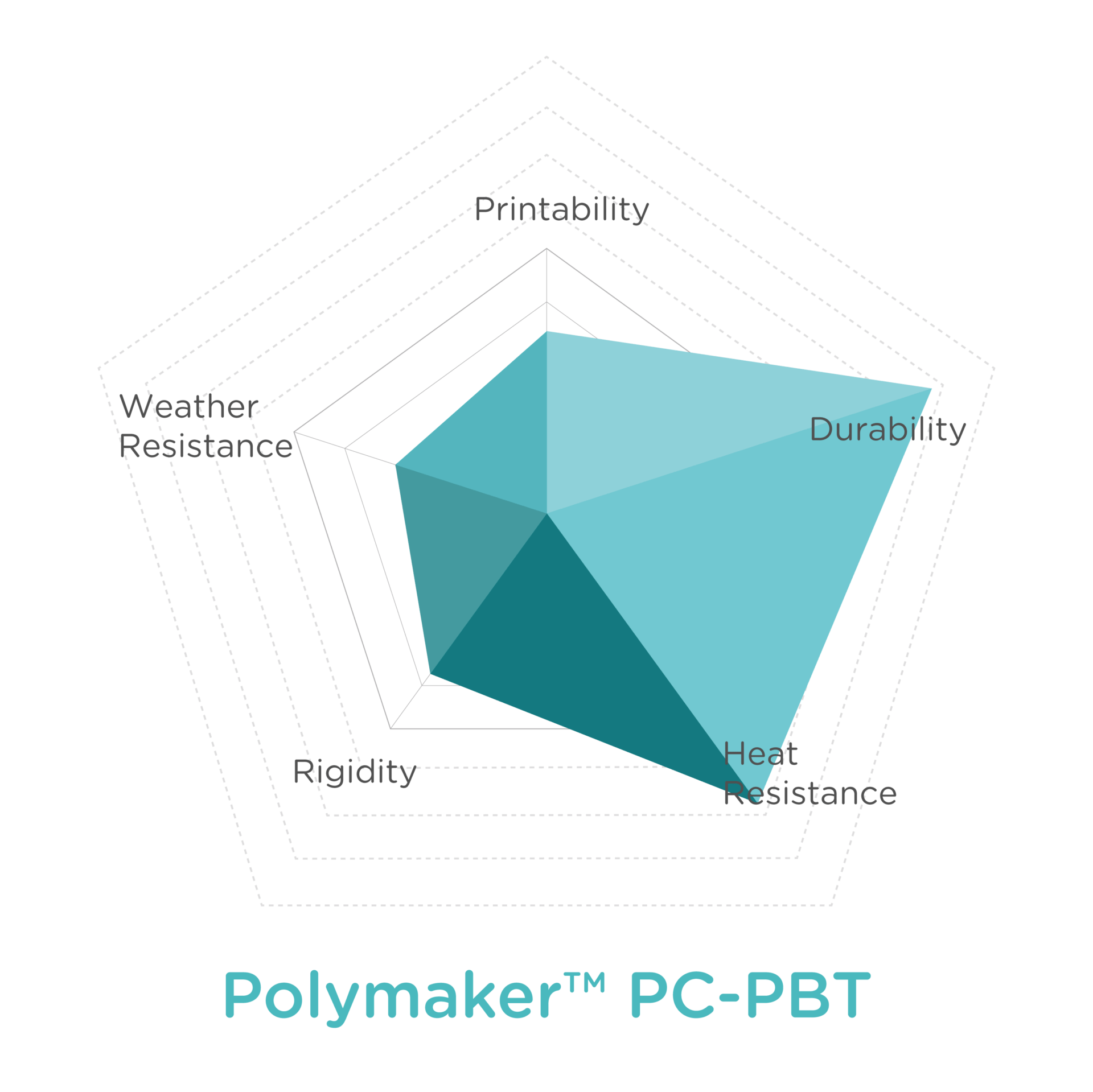

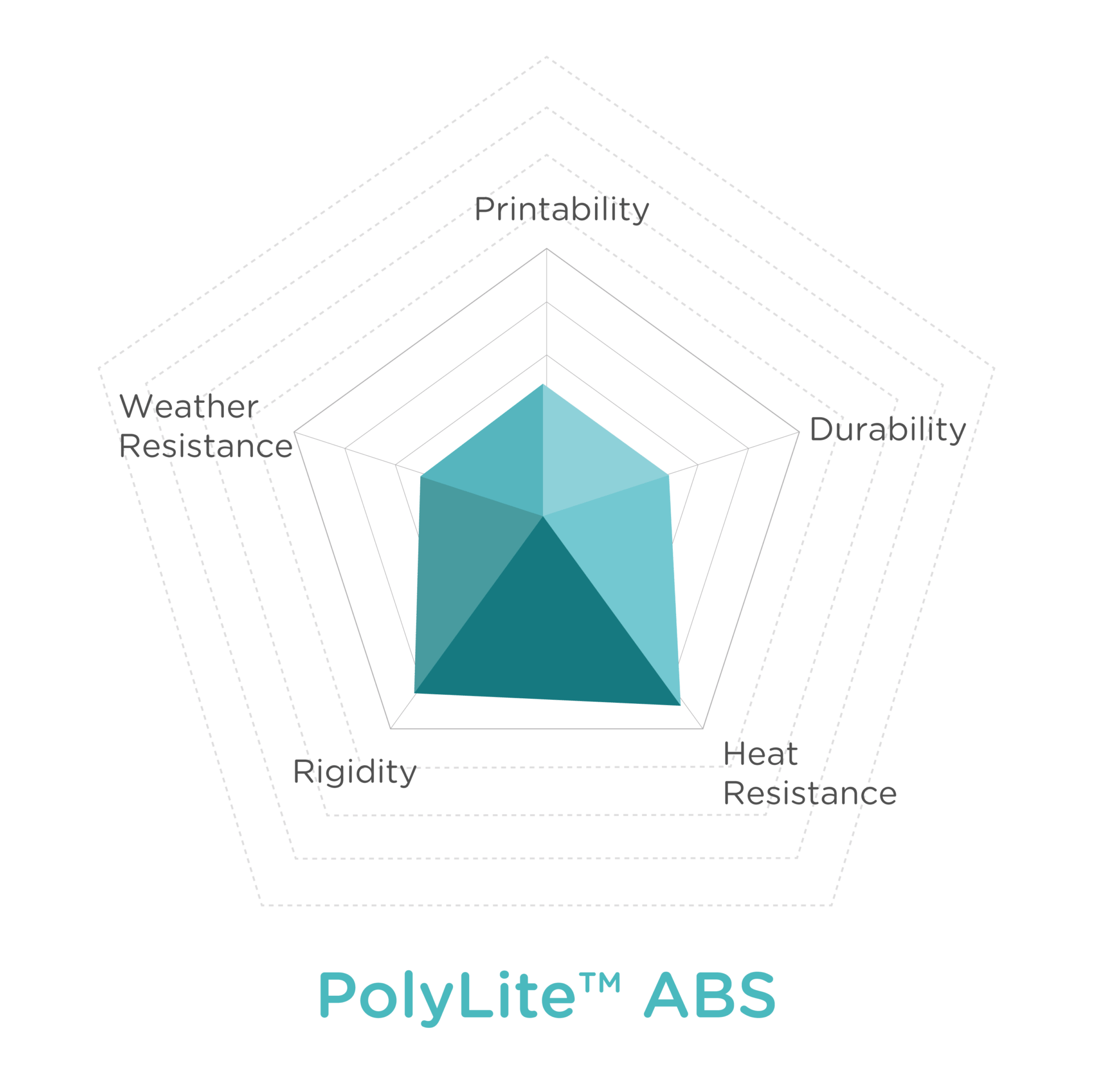

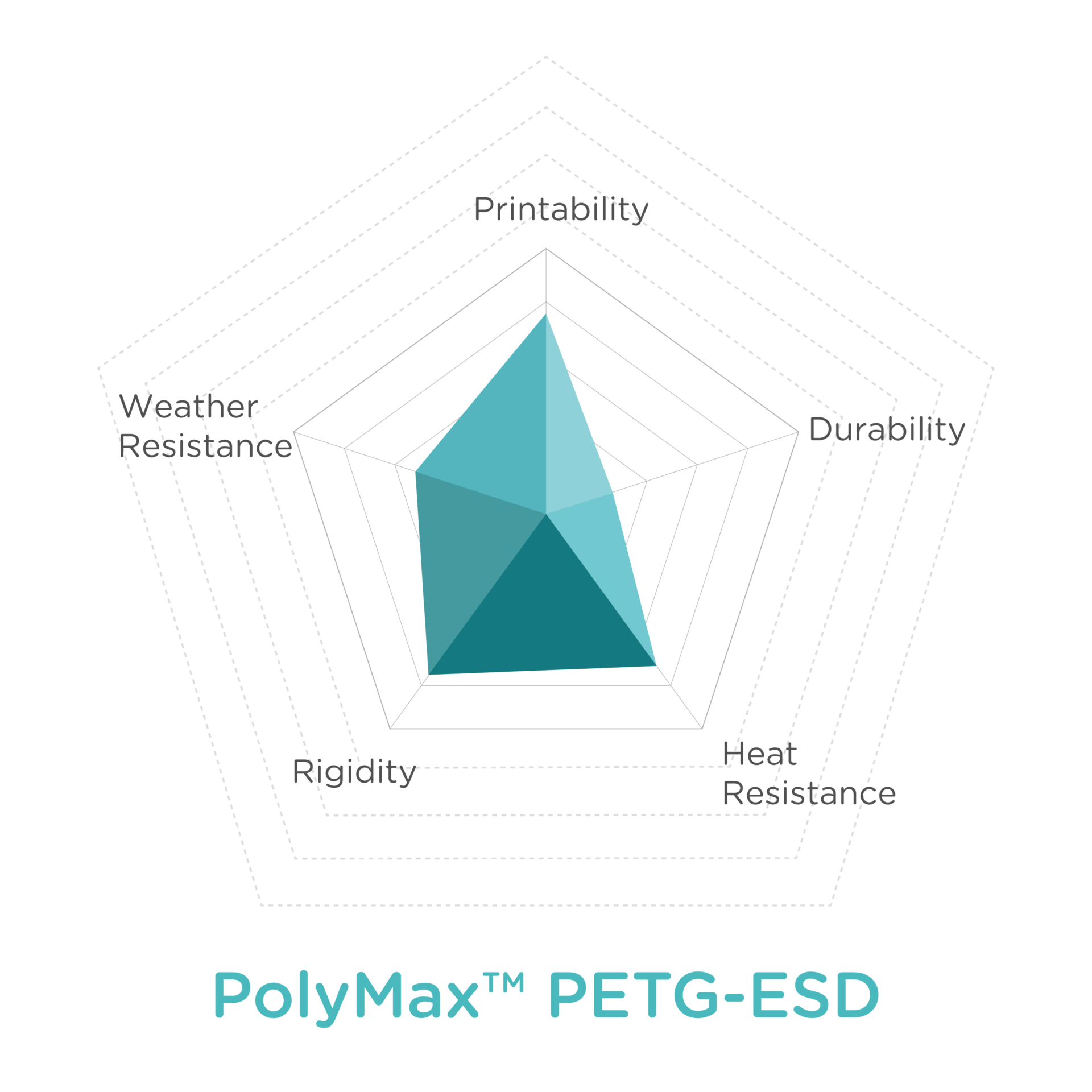

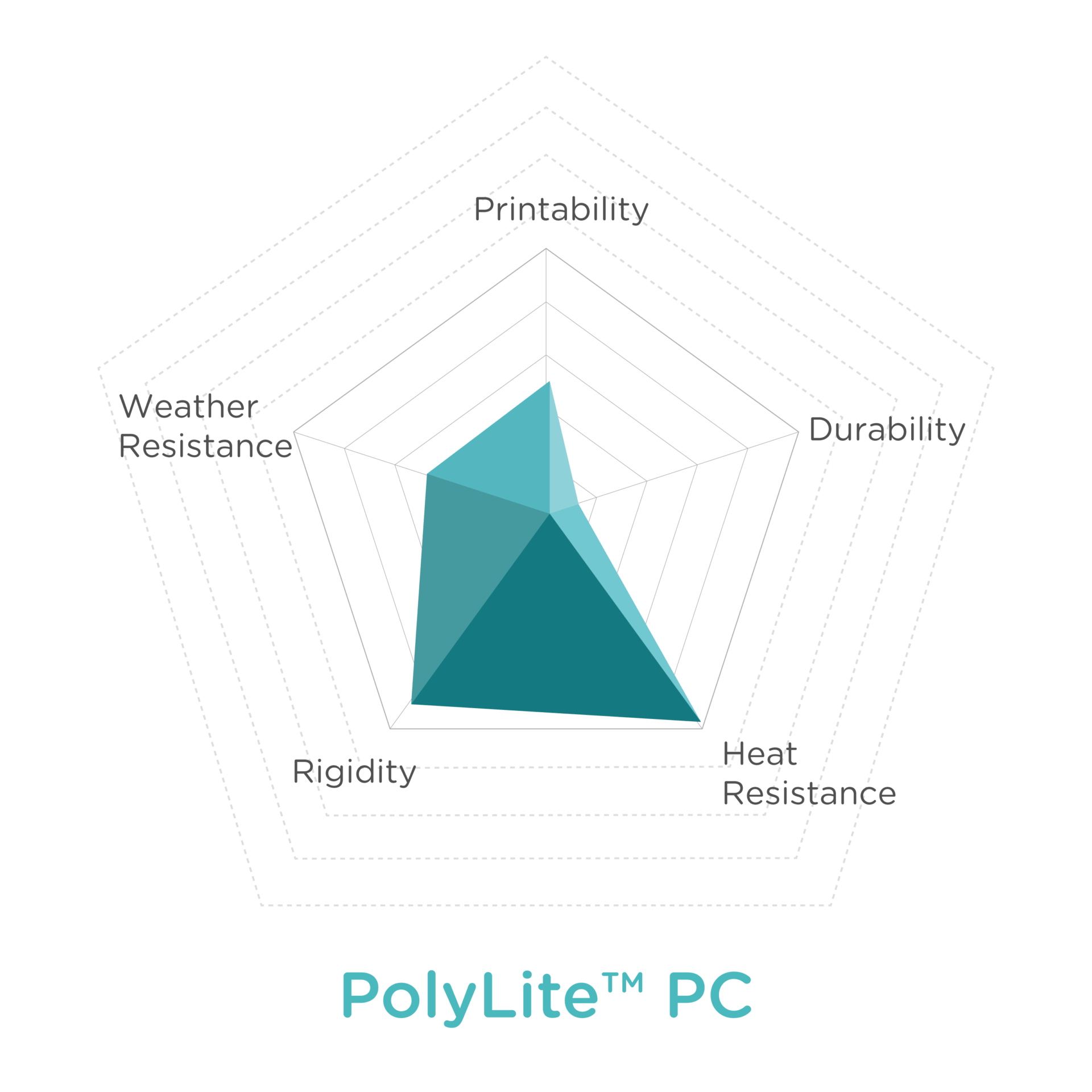

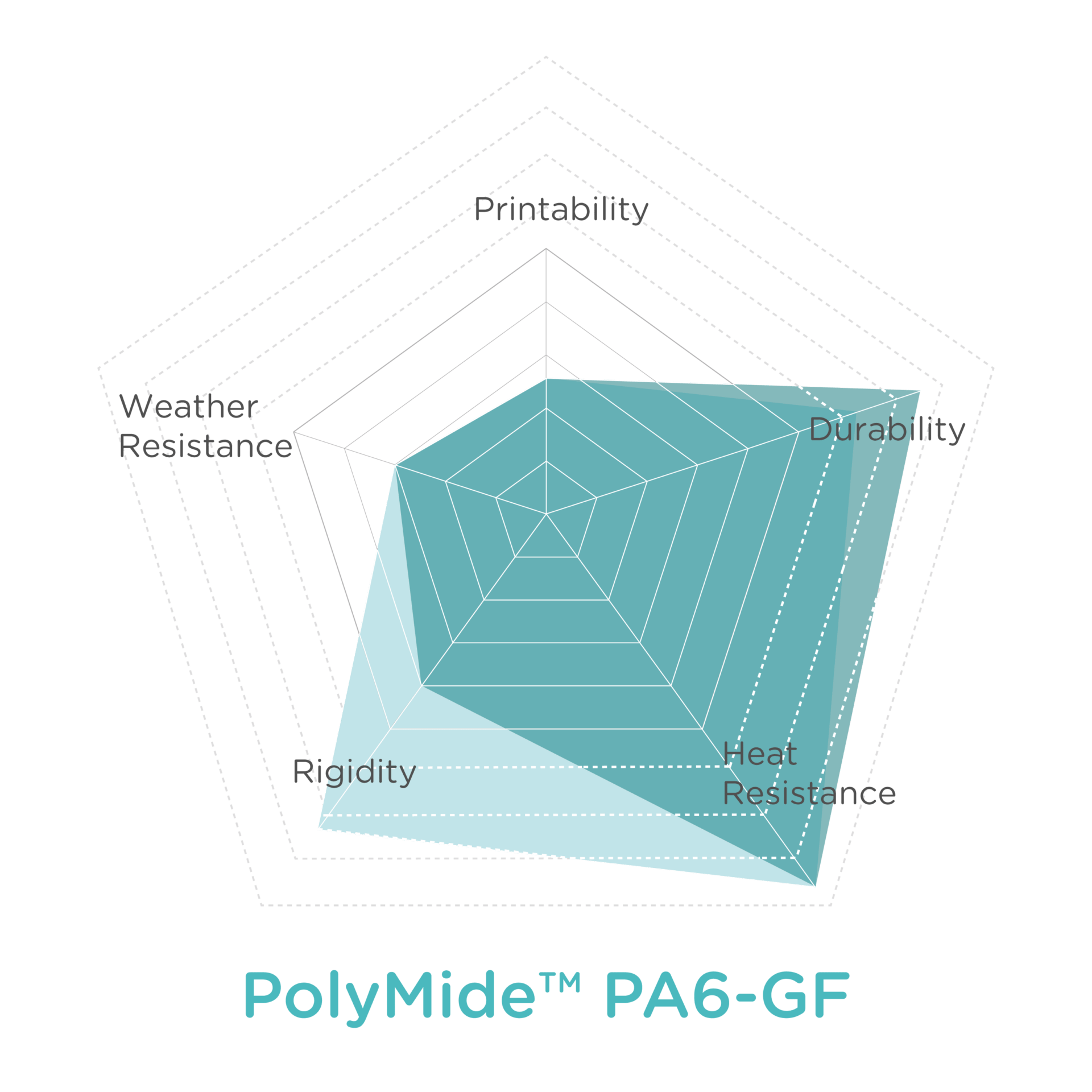

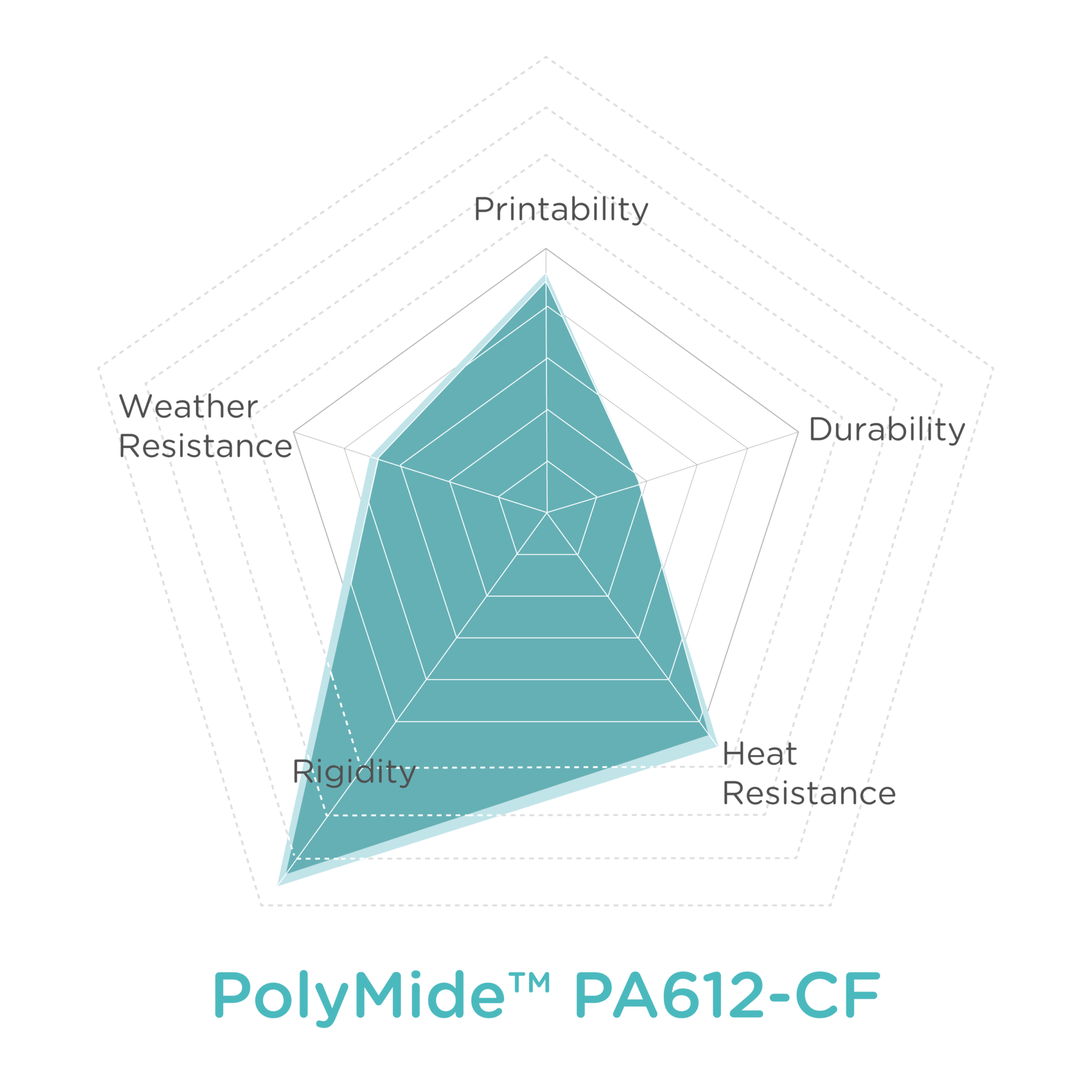

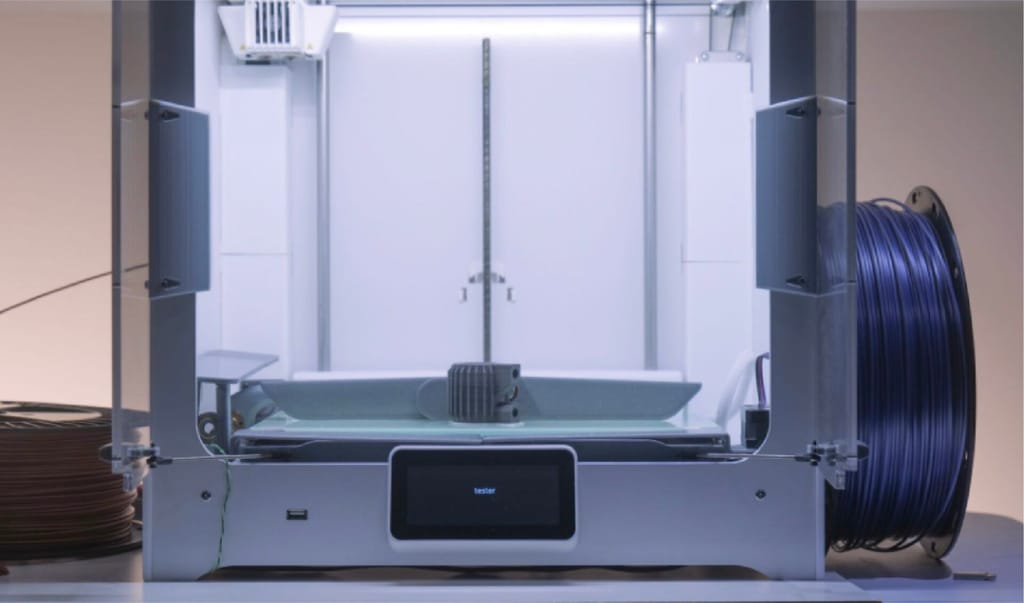

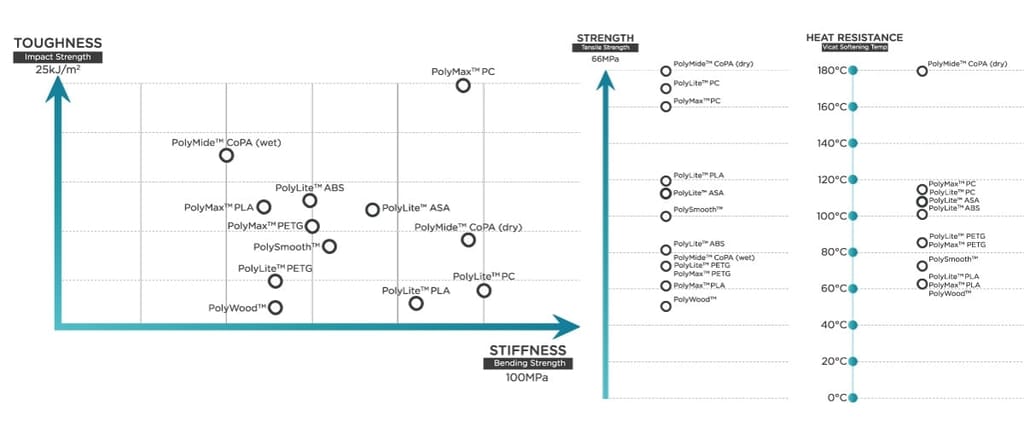

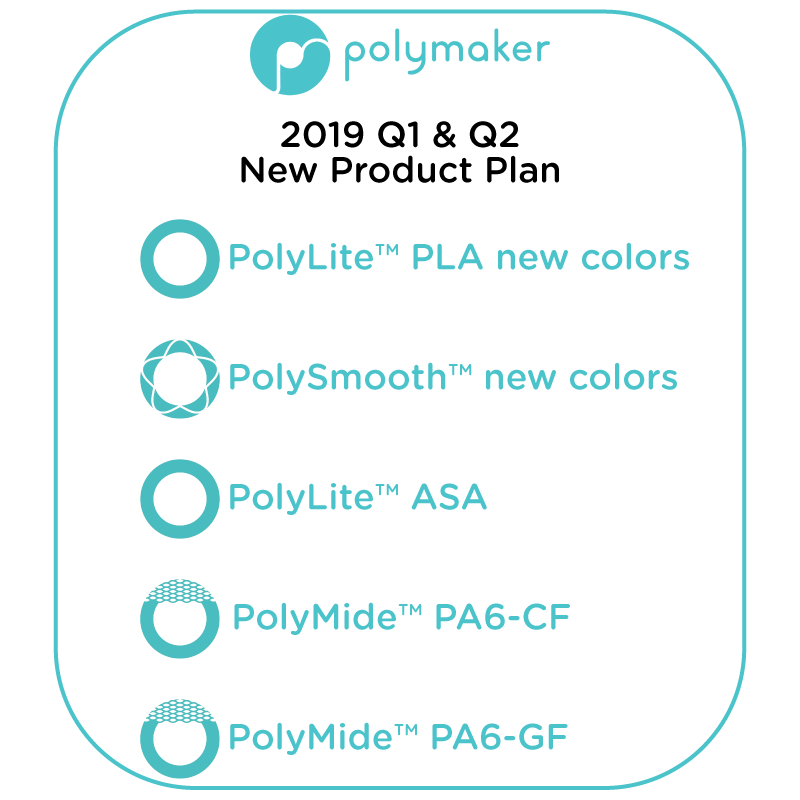

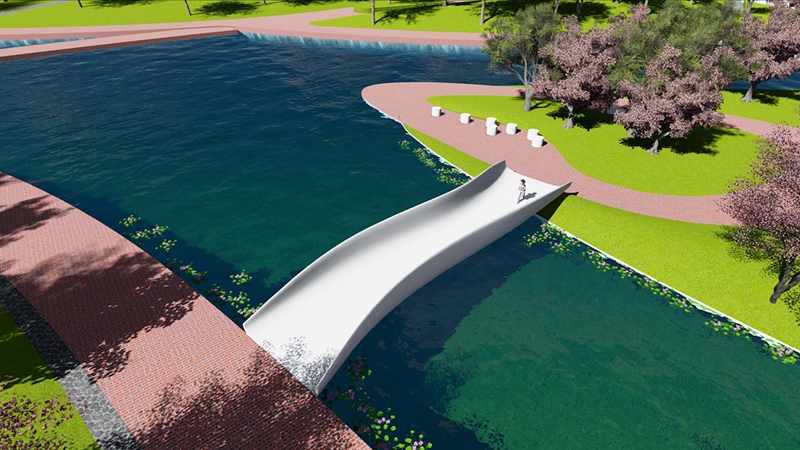

Polymaker just released footage of Shanghai Construction Group’s 3D printer in the process of producing a pedestrian footbridge, which will take 30 days to complete as it will be 15 meters long and weigh 5,800kg. SGC has a reputation for going big as they built the second tallest building in the world, the Shanghai Tower. The 3D printer was built by Shenyang Machine Group and the extruder system was manufactured by Coin Robotic (who also built the bed), together totaling some $2.8 million in investment. Polymaker Industrial developed the ASA (acrylonitrile styrene acrylate) plastic for the print, a material chosen for its favorable properties of weather and chemical resistance, thermal stability, and toughness. To determine the best plastic for the job, Polymaker 3D printed a 5-meter version of the bridge with several different compounds before choosing AS100GF for its overall strength and printability. The bridge will be rated to hold 13 tons or four people per square meter, so strength is vitally important.

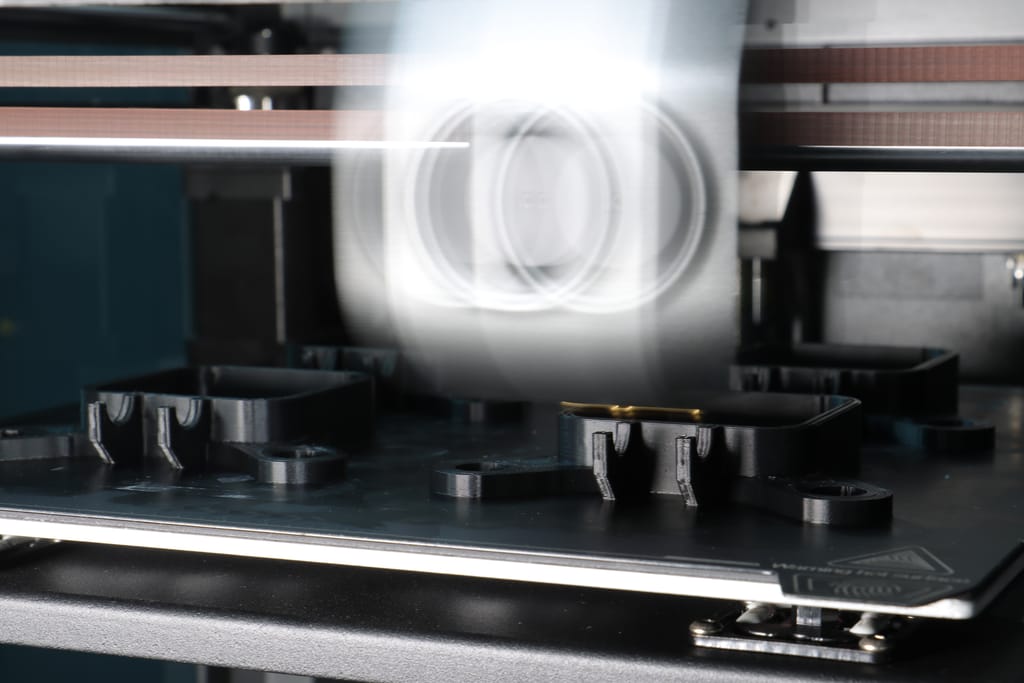

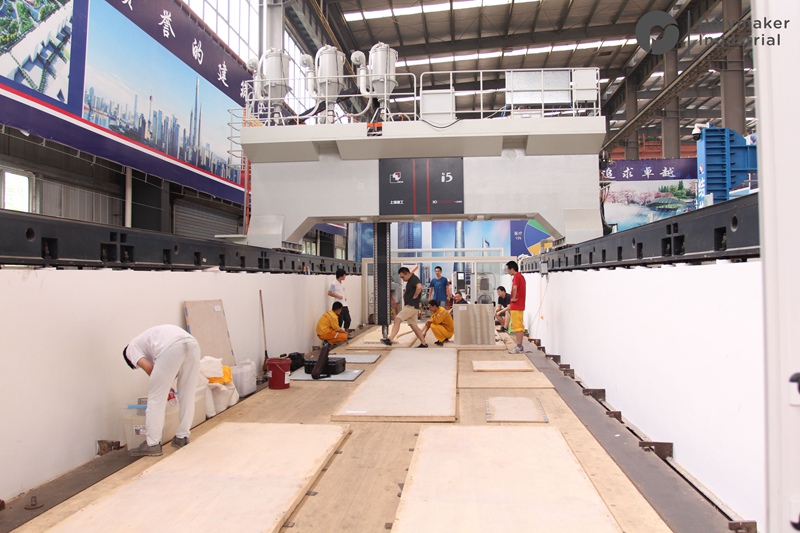

The plastic is 12.5% glass fibers by weight, adding strength and also reducing the warping effect that plagues large 3D prints. 3D Printing bigger isn’t as simple as just making a bigger printer because so much of 3D printing is related to heat retention and even heating, which becomes a trickier task the bigger the print/printer. In this case, the build chamber is 24 meters long, 4 meters wide, and 1.5 meters high, with a planned expansion to 3 meters high. That’s 144 cubic meters to keep heated, which is achieved by a large bellowed tent that moves with the gantry. The tent is heated to 38°C and blankets are placed on top of the print to slow the cooling process, allowing the polymer chains to relax without warping; the blankets also protect the print from dust. Yes, the build chamber is so large that technicians work inside the 3D printer while it’s operating to monitor the print and move the blankets.

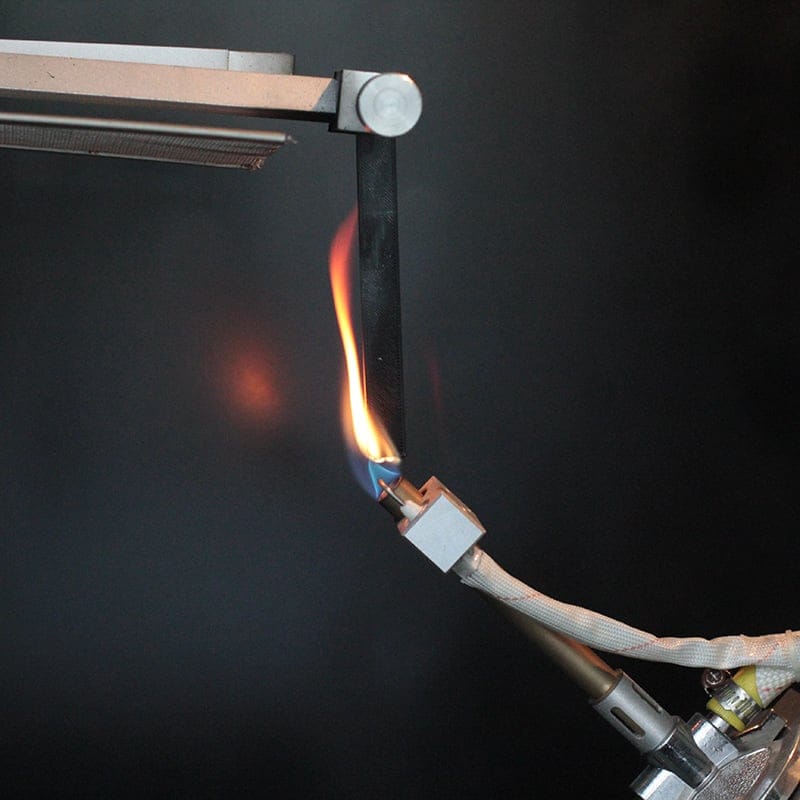

But heating is only one 3D printing issue that’s exacerbated by increasing scale as there’s also layer levelness as well as bed and layer adhesion. For layers to bond well, they should be joined when they’re at a similar temperature; on this print, each layer takes several hours, so the previous layer has cooled significantly by the time the extruder comes back around for the next layer. The blankets and the glass fibers help slow this cooling, but the print head does a lot of work here by reheating the print with four 600°C hot air guns aimed around the extruder. The air guns ensure the print is always hot around where the extruder is working for maximum layer adhesion.

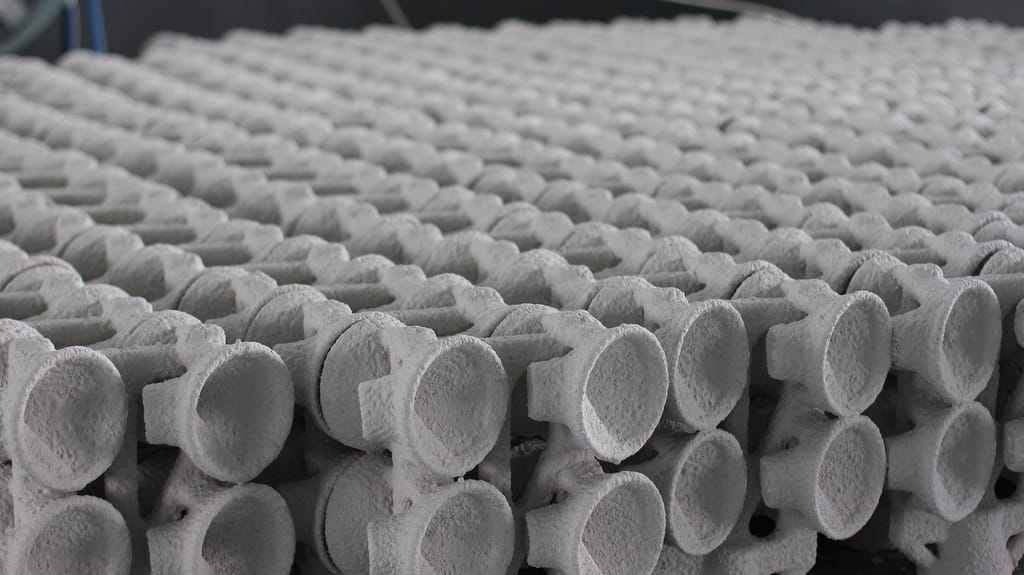

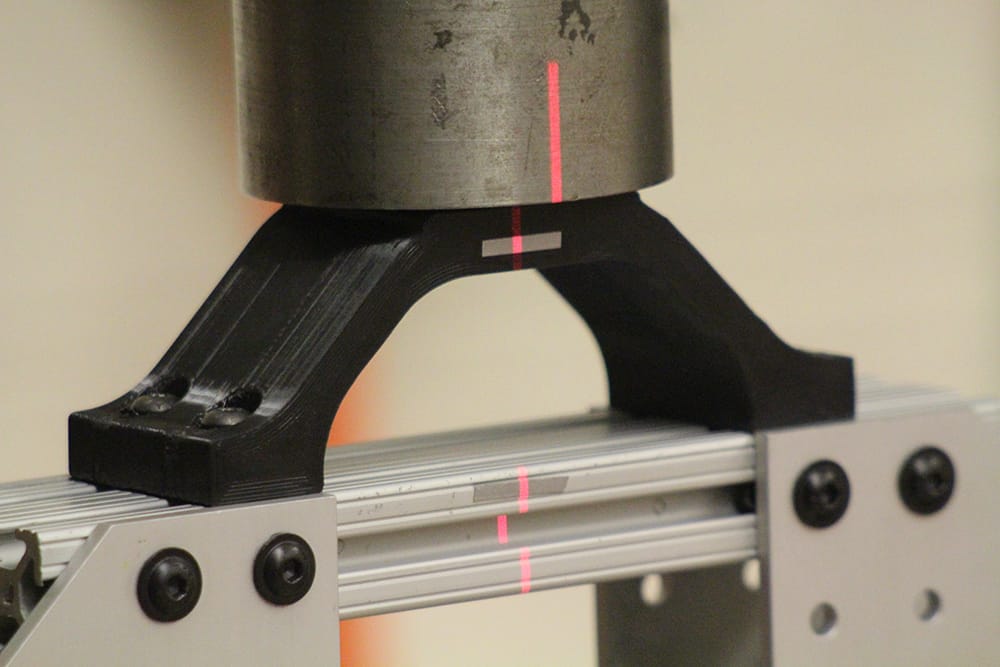

The layer levelness issue is solved here by a novel approach not seen on other 3D printers: tamping. Nozzles are round, meaning their extrusion is round, and when pushed flat as a layer they have a tapered top, which is not ideal for layer adhesion. For a desktop 3D printer with a nozzle size of 0.35mm, the taper is small enough to mostly not notice, but the SGC 3D printer uses a nozzle over 14x that size at 5mm so the tamping of the plastic right after it’s extruded makes a big difference in layer levelness and adhesion. And considering that, despite its gargantuan size and the fact that it’s extruding up to 8kg of plastic per hour, the printer is accurate to 0.1mm, those differences in levelness really matter. To get the first layer to adhere to the print bed, ASA pellets were glued to wooden planks that were then clamped to the steel bed. Sometimes the low-tech solution is the best solution.

A pedestrian bridge over a lake is a great way to showcase the largest 3D printed plastic object as it’s both an everyday, practical application and an interactive one that involves people touching and even relying upon (to keep them from getting wet) a 3D printed thing. Many people have never touched a 3D printed object and they still think of it as part fantasy and part future tech, so projects like this do a lot of good in terms of exposing the public to the reality and the possibilities of 3D printing.